When you’re short on time or have already played a long drawn out game of Commander, the table often agrees that the last game of the night should be a fast game of Commander. But what exactly is a fast game of Commander?

I don’t know about you, but most Commander sessions I play in have one or two games before someone suggests that we play a “fast” game. Whether it’s because we’re running out of time, or it’s just that we’ve played a lot of long, complex games already that day, a fast game is usually on the cards. Hell, sometimes it’s just because you only have time for one quick 60-90 minute game.

HOW LONG IS A GAME OF COMMANDER

The average length of a game of Commander is akin to the length of a piece of string. It heavily depends on the power level of the decks, the quantity of interaction, the win conditions, the skill of the players, and how laid back and casual the game is.

Broadly speaking, however, the average length of a game has shortened as the game has more cards printed for it. Decks don’t run out of gas as quick, and they have more win conditions than ever. There’s an oppositional traction, though, in that the quantity of game actions has also risen, with some decks taking ten minute turns that don’t actually lead them to a win, with some regularity.

WHAT DO PEOPLE MEAN BY A FAST GAME?

The issue with trying to have a good “fast game” of Commander, though, is quantifying what exactly that means. Discussions around expectations are nebulous at the best of times, and trying to qualify what a “fast game” is can be frustrating. Often it’s the case that one person’s definition is different to another’s, and the game ends sooner than some players would like – despite asking for a fast game.

The oft-discussed and recently maligned notion of Power Level is often the main influencer in picking a deck for a fast game. Generally people shortcut fast = high power, and while it’s not a heuristic I’m fully on board with, there’s a reason it’s the most prevailing one: it’s a good starting point. The issue with just choosing a deck that’s a higher power level than the one you played last is that it might not factor in the other’s interpretations of what constitutes a fast game. It’s also entirely based on your interpretation of power level, based on how you viewed the previous pod.

Win Conditions are pretty important to any pre-game discussion, and when agreeing on a fast game, it can also be crucial to discuss win conditions here too. Reason being, that even if one player has a linear, tutorable A+B combo deck, or an aggro deck as fast cEDH Winota, the other players in the pod still might not have a deck that holds a candle to it. They might have faster decks than the ones they’ve already played, but those decks still might lose to a lean, mean, min-maxed combo deck.

Still, that’s why communication is important. You gotta talk about your win conditions – yes, you should be open with your deck’s information, and not cagey, because if you’re not, it just creates mismatched expectations, and the potential for people to not trust you in the future. It might be that even if your faster deck is a quick A+B deck, that the rest of the table are fine playing against it even if they feel like they’re punching up. Mulligans, after all, have a huge impact on how anyone handles the decks across from them.

TERMINAL VELOCITY

Velocity is perhaps the better indicator now of how fast a deck is, and is kind-of an amalgamation of the Power Level and Win Conditions axes, but with additional emphasis put on how quickly your deck can generate resources. I like Velocity as my main talking point in pre-game discussions now, because it allows you to figure out exactly how sweaty any particular deck is.

When I say velocity, I generally mean the rate at which a deck progresses to the endgame. It captures both the general speed at which a deck can win, if not interacted with, and also the rate at which it accrues resources.

If we look at this very simple graph, it shows how resource generation can spike massively from turn 6 onwards, which is true for a whole host of decks that can be considered “fast”. They can do this by playing fast mana, playing cards that make treasure, playing cards that double resources, and having a strong new-breed Commander like Miirym, Dihada, Roxanne or Aesi.

A similar deck suggested for a fast game could have a resource generation curve much closer to this one. This kind of deck is more “fair”, and wants to win with creatures, and doesn’t go out of its way to play fast mana or draw handfuls of cards. It has a Commander like Jetmir or Jirina Kudro. It could be an Orzhov Aristocrats deck that doesn’t have the key pieces like Yawgmoth and Pitiless Plunderer. Or it could be an aggressive low to the ground deck like Krenko, Mob Boss, that has combo lines available. You can see that it reaches the previous deck’s velocity potential on turn 8 by turn 10, but that’s two whole turns slower, and the game is likely over by then.

It also has a much flatter “snowball”, and when you look back at the previous graph, you can see that the exponential explosion of resource generation past turn 6-7 means that those decks are potentially unbeatable if the game goes that long. The velocity that these latter decks bring to the table isn’t in resource generation, but in damage dealt, and pressure.

That’s why it’s important to talk about Velocity, and one of the reasons I think the ideal Commander pod consists of at most two midrange decks, with the rest being made up of aggro and control decks. The self-balancing nature of Magic’s rock-paper-scissors of archetypes can help to balance the differing velocities of decks.

QUANTIFYING VELOCITY

As we’ve discussed, velocity can be measured on multiple axes, with resource generation being only one of them. I mentioned “pressure” as another, but another way to look at it is how quick your deck can turn the corner.

I’ve got a sweet Henzie list that can generate resources quickly, but because it doesn’t run Terror of the Peaks or Gray Merchant of Asphodel, and because it doesn’t have Altar of Dementia or any A+B combos, the overall velocity of the deck doesn’t reach the same levels of exponential value that a build with those cards included would reach – or a Korvald, Fae-Cursed King deck.

Perhaps more key to the velocity discussion is the fact it isn’t aiming for a Turn 2 Henzie. A deck aiming for that would have a solid 13 plays on turn one, with 10+ being acceptable, in order to blitz on turn 3. My deck is more or less incapable of a Turn 2 Henzie, making it a key talking point in explaining the velocity of my deck.

Ultimately, velocity is something that you need to evaluate from playing games to truly understand. Once you do have a good vocabulary to describe it, though, you can begin to have better pre-game discussions.

THE CHESS CLOCK

While Magic players haven’t yet been accused of using questionable stimulation to achieve tournament wins, there are other things we’ve borrowed from Chess; namely, the Chess Clock.

No, we haven’t borrowed it literally, but figuratively. The chess clock is an omnipresent factor in games of Commander. Because Commander is a social game, taking up too much of the collective’s time with your own turns is a massive turn off, especially if you’re not winning.

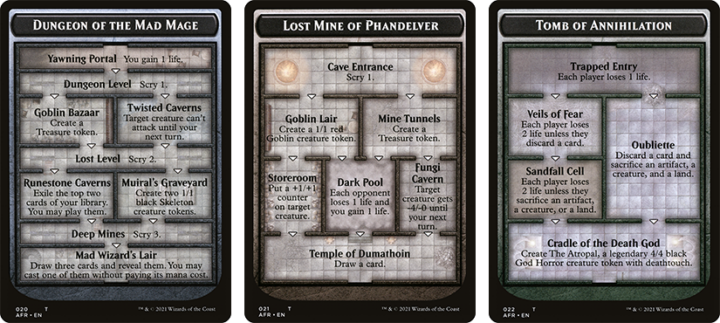

The problem is, Wizards seem bent on increasing the amount of busy-work Commander players have to keep on top of. The Monarch. Dungeons. Day and Night. The Initiative. Contraptions. Treasure, Clue and Food tokens. Stickers. And that’s ignoring the sheer number of game actions taken in average turns nowadays.

Gone are the days of waiting to untap with “two-spell turn” mana. Nowadays, you’re drawing cards, making tokens, putting counters on things, tutoring, consulting outside-of-the-game conditions, and all sorts.

The net result is that even without trying, the chess clock can be run dry by just taking standard game actions, and this roughly correlates with the resource generation aspect of Velocity that was mentioned above.

When you’re discussing what a “fast game” of Commander means, it might be an idea to pick decks that take a lower amount of game actions, on average, in order to get through turns quicker. This is all the more important if your playgroup is very slow at completing turn cycles.

Which leads me naturally on to Complexity. Complexity is the final factor to address today, and is an important factor to consider for having a good “fast” game of Commander. Maybe play your flicker decks that make token copies of things, require Infinitoken clones, and have a multitude of decisions to make on every turn of a turn cycle for the start of the evening. Complexity ties into the Chess Clock, and it’s responsible for long turns that don’t actually take many game actions.

It’s okay to have more reactive or variance heavy decks, sure, but keep in mind when someone asks for a fast game that they might not be the ones to bust out.

END STEP

Agreeing on what constitutes a fast game of Commander is a lot easier than you’d think. By consulting the advice shared today, and making sure you have a pre-game discussion that touches on Power Level, Win Conditions, Velocity, the Chess Clock, and Complexity, you should be able to figure out what a fast game means to everyone at the table, and pick a deck that fits the vibe.

Don’t be afraid to ask questions of other players if they’re not very forthcoming with information. It might not be that they’re being cagey; they might just not know how to express themselves well, and are nervous about getting it wrong. Help your playgroups grow and get better at communication and it’ll give you better games.

Kristen is Card Kingdom’s Head Writer, and member of the Commander Advisory Group. Formerly a competitive Pokémon TCG grinder, she has been playing Magic since Shadows Over Innistrad, which in her opinion, was a great set to start with. When she’s not taking names with Equipment and Aggro strategies in Commander, she loves to play any form of Limited.