Thematic, top-down card designs have become a real highlight of Magic in the past decade with parallels to Greek mythology, cyberpunk and even film noir. As a result, it’s no surprise that Wilds of Eldraine used so many fairy tales as its foundation.

This approach has become even more common in the wake of Universes Beyond to try and directly translate familiar characters and stories from outside Magic into recognizable game pieces. These cards act as fun little easter eggs for players to pick up on, and their unique mechanics often make them standouts within the set’s gameplay as well. But just how deep do the references run in these woods?

WITCH WITH A FROZEN HEART

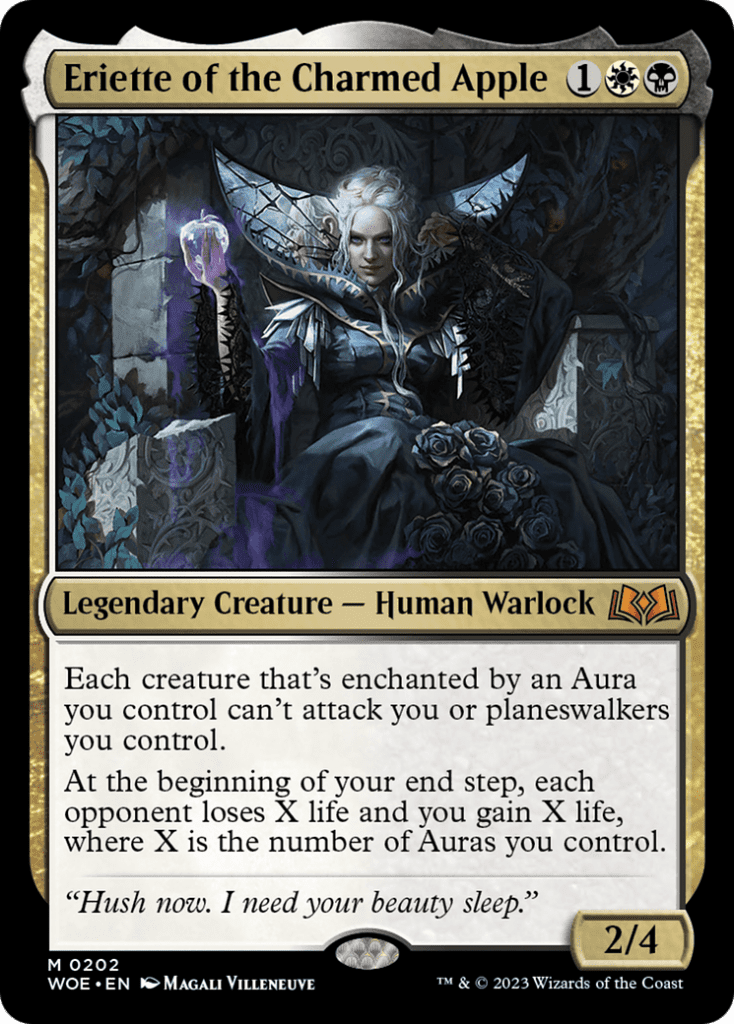

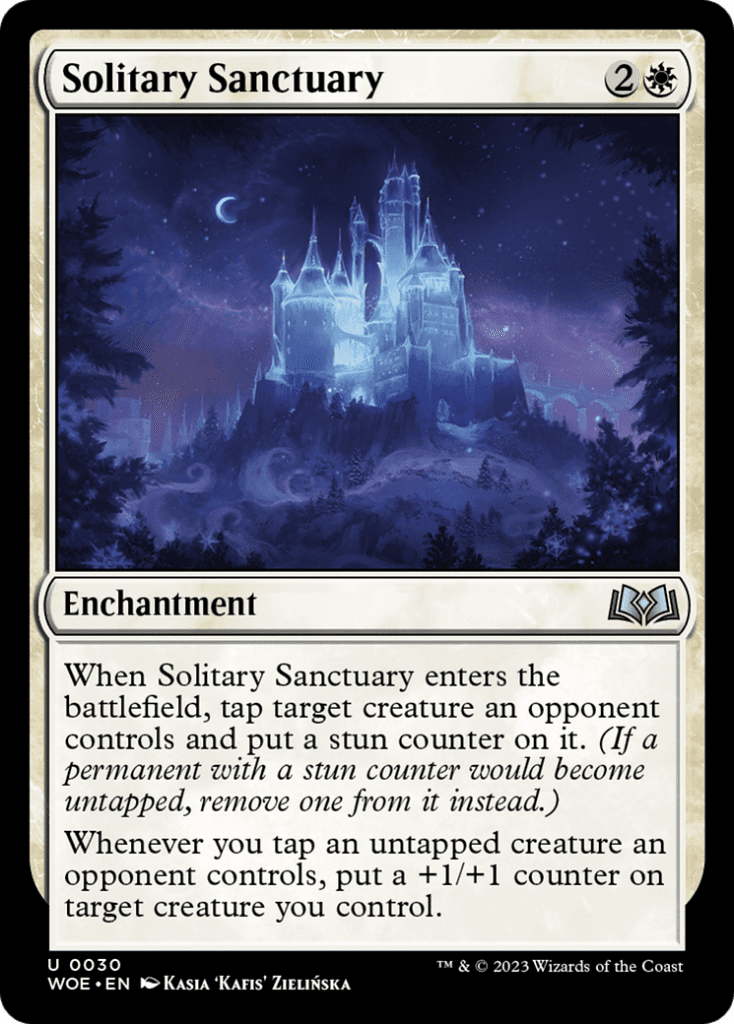

Hylda is one of the three witch sisters who conspired to create the curse of Wicked Slumber that grips Eldraine. Where her sisters Eriette and Agatha draw on the evil witches from Hansel and Gretel and Snow White, Hylda seems to be strongly inspired by Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen.

In that classic fairy tale, the Snow Queen is an aloof and mysterious figure who lures a young boy away from his friends and family to join her at an icy castle atop a frozen lake. To ensure he can survive there, she blesses the boy with a magical kiss so he no longer feels the cold — although she also makes him forget his loved ones to ensure he stays.

You might also recognize these story beats from The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe. Author C.S. Lewis borrowed heavily from Andersen to create his villainous White Witch, Jadis. But Hylda is actually closer to the original Snow Queen’s character, and her motivation is loneliness rather than outright evil. In the Wilds of Eldraine story, her menacing façade melts when she witnesses the depth of loyalty and friendship between young heroes Ruby and Kellan.

In the original tale, it’s the kidnapped boy who experiences a sudden change of heart after shards of glass from a wicked mirror get stuck in his heart and his eye. Their corrupting influence is what leads him to the clutches of the Snow Queen in the first place.

When his long-lost friend finally tracks him to the ice castle, her warm embrace melts the piece in his heart, and his own tears wash the piece from his eye — which makes him able to see and feel goodness in the world again.

There’s no explicit mention of dark magic being the cause of Hylda’s initial hostility, but Ruby’s loyalty to Kellan definitely melts her heart and causes her to relax her icy grip on the surrounding lands — neatly blending this story with even older legends regarding winter gods and the changing of seasons.

BASED ON A TRUE STORY?

Rats are an ever-present symbol in fairy tales, and they have been accorded an equally prominent place in Wilds of Eldraine.

The story of the Pied Piper is among the oldest stories of its kind and also seems based on a true, historical disaster. The earliest known recountings come from the 1300s, although all sources agree the events described took place a century earlier than that.

The familiar thread of the tale is clearly present even in the oldest, fragmentary telling. In 1284, a young man in fancy clothes walked through the town of Hamelin on a Christian feast day playing an enchanting tune on his flute.

With their parents presumably distracted at the feast, 130 local children flocked to hear the Piper’s song, following him as he marched through the streets. The Piper then led the children beyond the town wall to the nearby Calvary Hill where the whole procession promptly vanished from history.

The sudden and shocking loss of so many children was a sensational and scandalizing thing — enough that the story rapidly spread across Christendom and became a common folk story. But the reason for their disappearance is never directly explained, assuming the figure of the Piper is intended as allegory for what really happened.

Historians have suggested Crusader recruiters, pagan cultists or a mass emigration as a cause for the children of Hamelin to leave town. However, the most widely-accepted theory argues they simply died — and it is this grim interpretation that seems to have made it into Wilds of Eldraine.

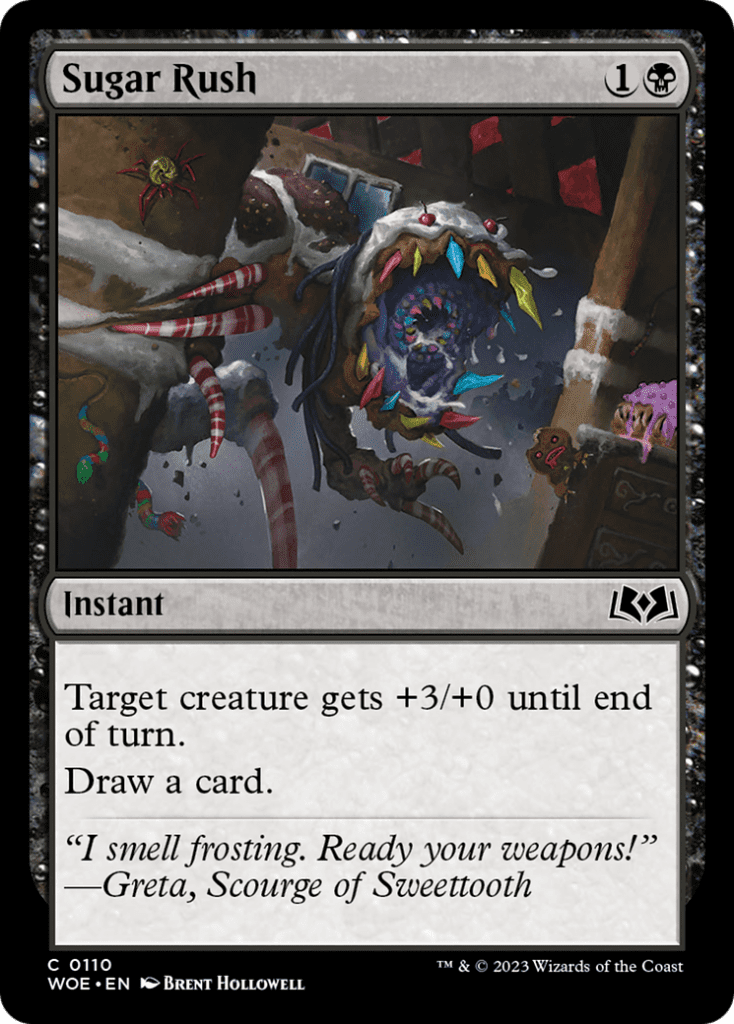

Totentanz is the German name for the Danse Macabre, or Dance of Death — a popular festival scene and artistic subject throughout Europe in the Middle Ages wherein the figure of Death dances merrily with corpses from all different walks of life. A child is nearly always included among the dancers, as a sad reminder that Death offers no special mercy to the young.

It’s not difficult to see the Pied Piper story as another entry in this medieval genre: the imagining of Death as a festive, dancing figure clad in “pied” (colorful) garb, luring the innocents of Hamelin away from their helpless parents. Reporting events in this abstract way certainly seems gentler on a community still reckoning with the sudden deaths of over a hundred children! This interpretation only seems more likely when you consider that Calvary Hill, where the Piper is said to have led the children, was where Hamelin town authorities held their executions.

But what about the most famous (and relevant) part of the modern Pied Piper myth: the rats? This aspect seems to have evolved between the 15th and 16th centuries, when it began to crop up in new texts across Germany. It seems most likely that as those retelling the story grew more distant from the original disaster in both time and space, they morphed it into a more general moral fable which would resonate with their audience.

This version of the Pied Piper becomes a magical troubleshooter, hired by the mayor of Hamelin to remove a swarm of rats plaguing the town. He first demonstrates his hypnotic pipe-playing by luring the rats into the countryside (or into the river to drown). But when the greedy mayor refuses to hand over his payment, the Piper returns to wreak his revenge — this time hypnotizing and stealing away the town’s children.

So the image of the Piper as a capricious commander of rats was cemented for all time. But he’s not the only leader of rodents recognised in fairy tales…

THE BIG RAT WHO MAKES ALL THE RULES

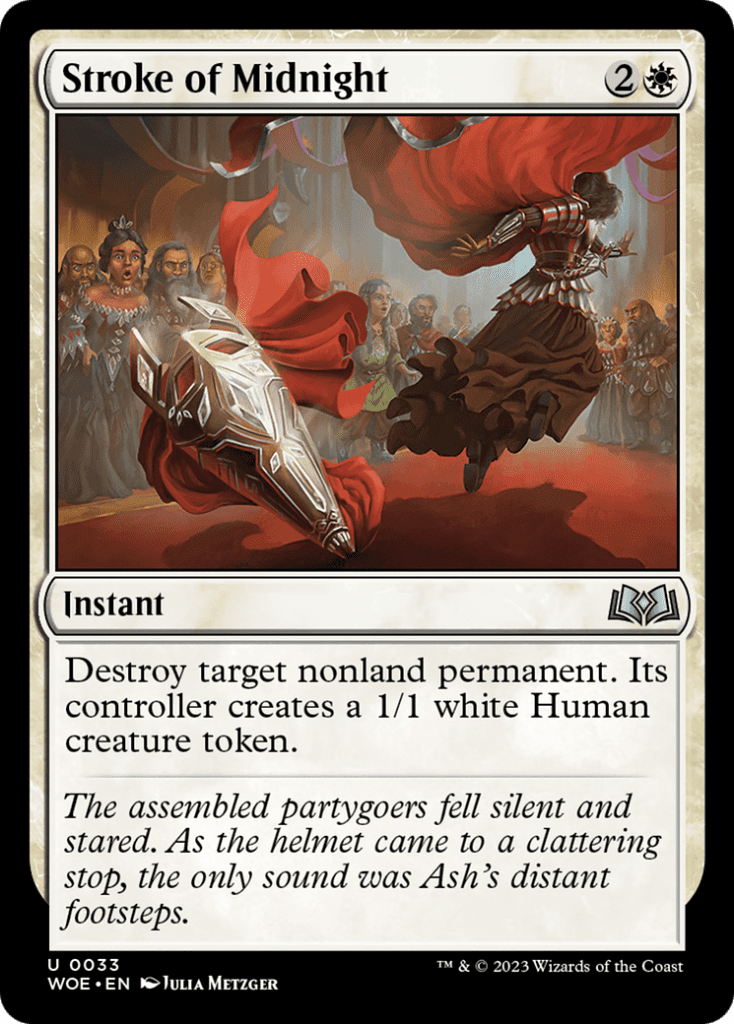

Given all that rats have come to symbolize in art and culture, a “Rat King” may not seem like an idea that needs further explanation. But the term does have some specific historical and folkloric meanings, at least some of which appear to have influenced the character of Lord Skitter, Sewer King.

The oldest usages of Rat King (or rather, Rattenkönig) describe a phenomenon where whole families of rats were born (or at least were later found by humans) with all their tails tangled together into a giant knot.

As unlikely as this sounds, famous specimens of such Rattenkönig surviving to group adulthood were found and preserved in museums across Germany. This led to the popular belief that other rats must be bringing their tangled brethren food and waiting on them as a monarch.

This Rattenkönig was a common enough idea to be recorded in a 1564 encyclopedia of folk beliefs and symbolism. An alternative depiction best described as a “rat hydra” appears in E.T.A. Hoffmann’s fairy tale Nutcracker and Mouseking, which provides the source for Tchaikovsky’s famous ballet.

The Nutcracker’s second act also seems to have inspired the Wilds creative team, this time with its Land of Sweets and the idea of anthropomorphic candy!

Still, other legends argued the tail-tied specimens were not themselves the Rattenkönig, but instead formed the royal dais from which the actual Rat King issued decrees. This is the version preserved in Rat King Birlibi, a German fairy tale published in the Napoleonic era.

That book describes Birlibi as simply a big fancy rat who lives the rich life of a noble and dines on “sugar and marzipan,” surrounded by his woodland court.

The symbolic reversal of a regal rodent manipulating and bestowing favor on human servants has made this Rat King an enduring cultural figure; one which pops up everywhere from Dark Souls 2 to Wilds of Eldraine!

A GREAT STORYTELLING TRADITION

That’s only the start of the fairytale allusions made in Wilds of Eldraine — each as storied as the last. Alas that we do not have time to explore them all here today.

But I find it fascinating to think about how long some of these ideas and fables have been kicking around the cultural zeitgeist, fundamentally unchanged through centuries of bedtime stories and children’s books.

These aren’t the gods worshiped by millions across antiquity, or great kings whose legends were inscribed on monuments, coins and palaces. These are small folk’s tales, preserved simply by their retelling through the oral tradition until they were eventually written down and codified — then surviving through parallel written versions for many more years, to finally be adapted into Magic: The Gathering.

It’s funny to think, but Wilds of Eldraine is now part of the same cultural record as those “eyewitness accounts” of the Pied Piper! It all goes to show that there’s more in common between people in all periods of history than one might think.

These stories and symbols have retained their power to fascinate us just as they fascinated our parents and grandparents. The only difference is we get some awesome and memorable Magic cards out of them — and that bit of progress feels juuust right!

Tom’s fate was sealed in 7th grade when his friend lent him a pile of commons to play Magic. He quickly picked up Boros and Orzhov decks in Ravnica block and has remained a staunch white magician ever since. A fan of all Constructed formats, he enjoys studying the history of the tournament meta. He specializes in midrange decks, especially Death & Taxes and Martyr Proc. One day, he swears he will win an MCQ with Evershrike. Ask him how at @AWanderingBard, or watch him stream Magic at twitch.tv/TheWanderingBard.