Over the years, Magic has invented a multitude of mechanics to build decks around, each with its own unique advantages, dedicated support cards, and memorable payoffs. But when all of those archetypes are thrown together into the grand melting pot of Commander, a few top-tier choices stand out. They offer versatile deck building options, consistent performance across different areas of the game and power ceilings which border on unbeatable.

Nobody can agree on what this week’s archetype is meant to be called, but EVERYBODY agrees how they feel about it. I often say that Commander is a format about playing as much Magic as possible per turn. When decks are built to do that well, you get games that feel like a drag race – ungodly powerful engines surging straight ahead to reach the finish line without so much as looking each other’s way.

But it is still possible to play defense in multiplayer, you just need to be efficient. You don’t try and shoot down every big play as it happens, you have to smother them and freeze them before they ever get off the ground. That is what a Prison (or Stax, or Stasis) deck does – it won’t win you many friends around the table, but it will win a lot of games.

ASYMMETRIC WARFARE

Slowing down multiple high-octane Commander decks is a herculean task, especially since those opponents will often end up co-operating to dismantle the prison you’re building around them. There’s certainly no way you’re going to win a resource trade 3-on-1 with traditional interaction – and if you do have that big an efficiency edge, you might as well just force through your own combo win!

To flip this to a winning equation, you need to block your opponents from building up their engine, limit their access to resources, and force them to be inefficient. You also need to do it to all your opponents at once, and preemptively, so that you don’t leave any window of opportunity for one of them to bust free.

Almost inevitably this means relying on permanents with disruptive static abilities that tax or outright prevent certain game actions. It’s a kind of card so signature to this playstyle that they’re usually called “prison pieces” or “stax pieces” in the community.

These effects come in several flavors. Some lock players out from taking certain actions or using certain mechanics, or at least reduce them to a fraction of their usual effectiveness. These cards are often the same ones used in Constructed sideboards; whether they cross over to this format depends on what actions they shut down and how central those are to the Commander metagame.

PUTTING THE “TAX” IN STAX

Then there’s cards which don’t completely block opponents from taking the targeted actions, but instead slow them down by charging an additional “tax” of mana (or other resources) every time. Most Commander players have seen how effective this principle is as applied to combat, thanks to classic staples Propaganda, Ghostly Prison, and Sphere of Safety.

But a true prison deck will also want to charge tax on deck searching, activating abilities, and just casting spells in general. When you consider how much Commander decks rely on infinite combos, long chains of cantrips, and using smaller spells to accelerate resource gain, making actions even slightly less efficient can really encumber most opponents.

Note that this does NOT include profiteering effects like Rhystic Study and Smothering Tithe, nor would I typically include a card like Manabarbs that taxes opposing life points. The goal is to prevent opponents from acting, not just punish them, and damage-based taxes only do that when you combine enough of them to add up to lethal (a variant strategy known as Group Slug).

The last and least common type of prison piece go a step further than taxing how opponents spend resources and instead attack or limit the actual resource production. This includes the oldest and most brutal pieces, like Winter Orb, Stasis, and Chains of Mephistopheles, but can also stretch to effects like Rule of Law or Price of Glory. Outright land destruction like Armageddon doesn’t fit our typical model of permanents-with-static-abilities… but at the very least we can admit that those spells complement our overall strategy.

All of these prison pieces work well in tandem, and especially in multiples. The only time they don’t synergize is when two lock-out type effects target the exact same thing, and even then you’re gaining a valuable layer of redundancy against opposing removal. Granted, the more pieces you can assemble the harder it becomes for opponents to fight back – which is why you should prepare to be targeted early and often.

THE SCHOOL OF HARD KNOCKS

Most of the time, your deckbuilding process is guided by your choice of win condition, or at least your commander. But for all intents and purposes, gumming up the board with a bunch of prohibitive prison pieces IS our win condition. Figuring out how to end the game so they can’t come back is absolutely important, but it’s more of the cherry on top.

What matters is ensuring that initial buildup of prison pieces is swift and decisive. Think of it more like a creature curve in an aggro deck than a true combo; we need redundant early game tax effects so we’re always slowing opponents down before they can pull away, then we can follow up with some more expensive or specific haymakers.

There’s enough prison pieces in Magic’s back catalogue to reach that density if access to older cards is no issue. Another great option is to make your commander a prison piece, ensuring this crucial step in the game plan is always on time. Gaddock Teeg, Lavinia, Azorius Renegade, Hokori, Dust Drinker and Grand Arbiter Augustin IV are some good choices in this vein.

Another essential ingredient is some efficient, traditional early game interaction – spot removal, counterspells, defensive instants, even board wipes. Yes, I did say right at the top that you can’t lock down multiple opponents playing these types of cards, and that’s still true. But even the best prison pieces cost two or three mana, and it takes a few of them to really put good decks off their game. That means opponents will have a chance to get rolling (or disrupt your buildup) before you can really get the cuffs on them tight.

That’s where this traditional interaction comes in – to help us fight as efficiently as possible in the crucial early turns. A won interaction on turn two might mean our Thorn of Amethyst or Stony Silence lives to turn three, which means our opponent lacks mana to cast their commander on curve, which then buys us two more turns to get prison pieces down before they can threaten to pop off.

Similarly, if one opponent opens with mana accelerants into an early value engine, they might be able to answer our prison pieces as fast as we play them, or just generate enough resources to win through them. This is why having some of those hard-lock pieces is important – no amount of mana will let them graveyard combo through Rest in Peace. But it’s just as useful to have a way of undoing any progress they make in building a board once you’ve stopped the forward momentum, thus reducing the risk should they find an answer for whatever lock piece is holding them up.

Defensive interaction, particularly effects which can protect noncreature permanents, are potentially the most impactful of all. In a lot of games, the most important stack interaction will come immediately after you resolve your first or second prison piece, as opponents recognize that every new card you play makes it harder to fight back. Any attempted removal you block is a huge economic and psychological blow to the rest of the table, so cards like Veil of Summer or Apostle’s Blessing are not to be overlooked.

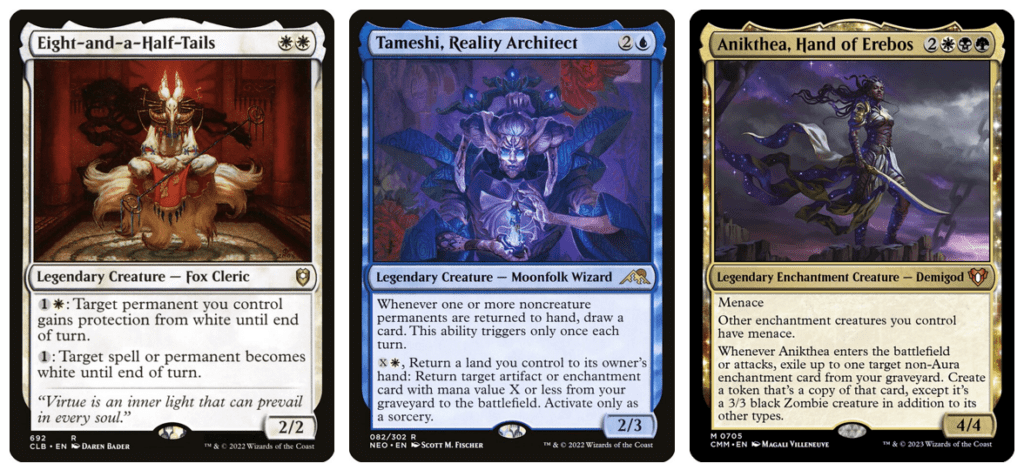

This is also a great role your commander can slot into, particularly if they’re able to protect (or resurrect) prison pieces on demand. Eight-and-a-Half Tails, Tameshi, Reality Architect, both versions of Teshar, and Anikthea, Hand of Erebos are all good options, depending on your exact build.

That last part isn’t just a platitude, mind you – you need to choose your game-closing effects extremely carefully when your own deck is liable to counter them.

WHAT IF THEY WON’T JUST GIVE UP?

While I think you should genuinely encourage opponents to concede once the prison effects have stacked up enough, it’s still polite (and tactically sound) to have a way to win games under your own oppressive regime.

One way is to think about it like a control deck: assuming you have infinite time to get the job done once the game is locked up, go for the most irresistible and foolproof plan possible. It could be as straightforward as leaning on a commander like Koma, Cosmos Serpent, or you could be putting filibuster counters on Azor’s Elocutors. Anything more threatening than attacking with hatebears and faster than waiting for opponents to deck out is a potential champion in these circumstances.

The other, less fair-minded choice is to find a way to cheat the parity of your prison effects, and then canter to a win while everybody else is still stuck in the quagmire you created. This might work just by playing prison pieces which don’t have parity to start with (Blood Moon in a mono-red deck) or you could pick a commander who helps you evade the worst of the restrictions. Xolatoyac or (appropriately) Jorn, God of Winter can forcibly untap your permanents in spite of Winter Orb. Taigam, Ojutai Master, Surrak Dragonclaw or Thryx, the Sudden Storm can punch through lock pieces like Dovescape or In the Eye of Chaos.

Those sorts of commander abilities aren’t very common though, so it might be easier to just intentionally leave yourself a little gap in the prison wall. Choose your win condition, ideally something a little obscure, and then just avoid including prison effects which would make it impossible to execute that plan. You could even fit in some prison pieces that do block your own victory, if you’re confident you can then sacrifice or remove them when you’re ready to go for it.

For example, classic Food Chain combos only rely on you being able to cast creature spells and activate mana abilities, neither of which are commonly locked out by prison effects. Even tax effects like Lodestone Golem can be counteracted with a discounter like Urza’s Incubator or Animar, Soul of Elements.

Decks that can string together lots of extra turns are also very good at evading most prison effects, so long as they aren’t relying on a more vulnerable mechanic (like graveyard combos) to get there.

THE ONLY GOOD PRISON IS A CARDBOARD ONE

For a lot of people, Commander feels like an escape from the zero-sum harshness of 1v1 Magic. So it’s not surprising that prison decks suffer from the kind of loud, widespread disapproval that should be directed at prisons in real life. But don’t listen to the haters: the average Commander table is witness to acts of magical depravity and gross mana fraud that no society should condone. By forcing them to work harder for the win, they’ll end up enjoying it more – or at least that’s what I tell my vanquished friends from atop my suffocating pile of enchantments. Have a happy Stax-mas!

Tom’s fate was sealed in 7th grade when his friend lent him a pile of commons to play Magic. He quickly picked up Boros and Orzhov decks in Ravnica block and has remained a staunch white magician ever since. A fan of all Constructed formats, he enjoys studying the history of the tournament meta. He specializes in midrange decks, especially Death & Taxes and Martyr Proc. One day, he swears he will win an MCQ with Evershrike. Ask him how at @AWanderingBard, or watch him stream Magic at twitch.tv/TheWanderingBard.