Tales of Middle-earth proved how well Magic can adapt itself to capture the identity of other blockbuster media products through its design. As with the Warhammer 40,000 Commander decks last year, Wizards of the Coast bet a lot on their ability to draw in new and returning players from among fans of the source material.

It’s a confident move; Magic can be hard for a novice to understand on its own terms, let alone feel a genuine connection to the media they love. But that’s what these Universes Beyond products have consistently managed to do.

The secret to this success, and the success of future Universes Beyond products, is in top-down design, which is woven into Tales of Middle-earth at both the set and card level.

FAMILIAR STORIES IN A NEW LANGUAGE

In the past, I’ve discussed the role of top-down design in previous sets like Throne of Eldraine, Crimson Vow, or Adventures in the Forgotten Realms. Like Tales of Middle-earth, those sets made a specific effort to reference well-known stories and characters in their card mechanics.

Choosing card names and artwork that fits the source is one thing, but it’s the extra effort to try and design cards in ways that are recognizably tied to the original concept and really makes a product feel like “the fairy-tale set,” or “the Norse mythology set” or “the Dungeons and Dragons set.”

It’s all possible because Magic has built up a very strong, internally consistent design “language” over the years. Even casual players develop a sense of what a +1/+1 counter “means” in the flavor of a card, or how much power a non-legendary, non-mounted human creature “should” have.

There’s no particular reason you couldn’t make a six-mana green Elf that destroyed lands, and a lot of card games wouldn’t think twice about printing that card. But Magic wouldn’t — that’s too much mana for just a single elf, and not even the various corrupted and dark elves of the multiverse would betray their connection to nature by destroying lands. That card would be a Wurm instead, or maybe a Beast.

Not all of these design-flavor rules are absolute, but even when Wizards decides to break them, it communicates that something is corrupted or inverted in the lore of that set. Building up the connection between lore and mechanics has a multitude of benefits for every set, but it’s especially important when “translating” concepts and characters from other IPs into Magic’s design language.

Elves in Lord of the Rings are known for their long view of history. They act based on foresight and prophecy rather than the momentary concerns of men. Even a brand-new player can understand how that translates to scrying — a mechanic that literally lets you “see the future” and position yourself to take advantage. So, of course, that’s what the Elf cards in Tales of Middle-earth are designed around.

Furthermore, the Elves of the Third Age are an elite yet dwindling force; a stark contrast to their usual Magic role as green’s cheap fodder creatures. So in Tales of Middle-earth, the common 1/1 mana dork is a human while the Elves are mostly higher on the curve.

Both the individual mechanics of the elf cards and their placement in the overall set resonate with the details of the source material, and that’s what makes Universes Beyond so effective at adapting different IP.

LEGENDS STAND OUT

With the commons and more generic creatures of the set, Wizards relied on matching flavorful creature types and set mechanics to build up the identity of each color. Food tokens for Hobbits and denizens of the Shire, amass for the armies of Mordor and Isengard, scrying for the elves, sacrifice effects for the hungry beasts of the forests and moors.

But top-down design is definitely more of an art than a science; sometimes it’s even more a cryptic crossword puzzle with unique and idiosyncratic answers. When they need to anchor a card design not just to a specific milieu but to a beloved named character, Wizards will try all sorts of tricks to make that connection explicit.

If you or I were asked to make a Shadowfax card, I think most of us would get as far as “Legendary Horse that buffs other horses.” That’s what it means to be a “Lord of Horses” in Magic-ese, after all.

And perhaps I would have thought to add an ability that lets Shadowfax carry a smaller creature into the fray — and to also make certain that Gandalf, White Rider has low enough power to make use of it. But I doubt I would ever have thought to specifically insist the card be printed with some rarely-seen reminder text just because Gandalf’s quote instructs him to “show them the meaning of haste!”

That’s closer to wordplay than it is building on the past conventions of Magic design, but it’s the kind of immensely satisfying detail which cements this card as really being Shadowfax, and this set as a proper adaptation of Lord of the Rings.

RETOLD ON THE TABLETOP

Gandalf himself is a good example of how Tales of Middle-earth worked around an inherent limitation of Magic design “translations”: scope. There’s only so many abilities you can put on one card, and for more complex and storied figures it’s not possible to reference everything important in a single card.

Not to mention there are additional limits on these designs. How can you capture Gandalf’s triumphant transformation into the White Wizard when the set doesn’t even have transforming cards?

Well, while it would have rocked to actually flip Gandalf the Grey into Gandalf the White, Wizards has plenty of other ways to evoke movement, change or time in order to recreate a character’s biggest moments.

By using the play patterns of the card to mimic the beats of a plot or character arc, designs like Gandalf, White Rider provide the most satisfying and obvious flashes of connection between the source and the set. Seeing these miniature stories re-enacted in actual gameplay, with recognizable results, is the ultimate validation for the set.

Denethor is another great example from Tales of Middle-earth, with his entire character arc packed into a few efficient lines of text. First, he scrys the future in his palantir. Then, despairing after Sauron’s manipulation, he sacrifices himself, abdicating the monarchy of Gondor to his chosen successor.

Even the decision to use red mana in the cost of his sacrifice ability (and have the effect be something we’d associate with a fiery missile) is a genius bit of efficient storytelling that makes the card feel so much stronger in its final form.

SEND IN THE SAGAS

Of course, if we’ve decided it’s best to design cards that re-enact the plot of the source material through turn-by-turn gameplay, then Wizards has already created a card type to achieve that.

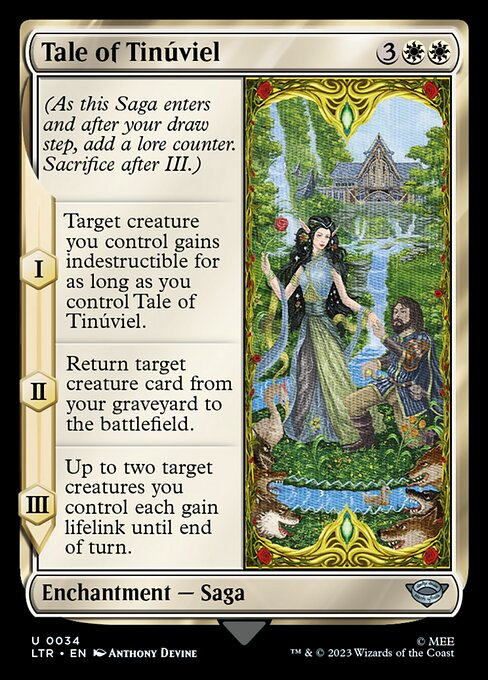

As their name suggests, Saga cards have play patterns that lend themselves to top-down translations of entire stories rather than individual characters or events. Due to their high word count and complexity, there’s only so many slots for these enchantments within a set, and Wizards made some astute decisions about where Tales of Middle-earth should deploy them.

Since the Lord of the Rings set should feel like it’s taking place in the same time period as the books, Wizards has mostly used these Sagas to highlight stories from elsewhere in Middle-earth history — including that of The Hobbit!

There and Back Again uses all the top-down design techniques we’ve discussed to summarize a ~95,000 word novel in three triggered abilities — with an admitted focus on the role of Smaug.

First chapter: a protagonist embarks on an arduous journey, moving ever forward, and is tempted by the Ring along the way. This might have been best represented by saying the creature “must attack,” but “can’t block” is similar enough and more flexible in its use.

Second chapter: the adventurer reaches their destination — a “lonely” Mountain. The design team gets a polite golf-clap for that one.

Third chapter: Smaug, master of the mountain, appears. Upon his defeat, we loot 14 treasures from his hoard — one each for Bilbo Baggins and his thirteen dwarf companions!

Each of the 14 Sagas designed for Tales of Middle-earth and its Commander precons show a similarly loving level of detail, and they remind me of why Sagas are such an invaluable card type for Magic.

They are one of the most effective options in a storytelling toolbox that allows these top-down design sets to engage with the source material at every level of detail; from representing individual combatants only implied to exist by the presence of battle scenes to dealing with entire histories on a single card.

THE MINDS BEHIND THE MAGIC

This thoroughness of effort in designing even common and uncommon card effects for Tales of Middle-earth is something worthy of applause. Almost every single card has some identifiable root in the books or the movies, be that Bill Ferny selling you a horse or Legolas keeping a more accurate track of his kills than Gimli does.

This set may not actually represent a great shift in the internal processes of Wizards of the Coast. Figures like Mark Rosewater often discuss new sets in terms of specific “peak gameplay experiences” that have been baked into the cards. They clearly understand how much this resonance of flavor and mechanics can carry the set for players regardless of whether or not it’s part of the Universes Beyond imprint.

But perhaps because Tales of Middle-earth adapts such a well-known and richly detailed story as Lord of the Rings, this time we have the context needed to identify all these little touches and their significance — to really appreciate the rich, expressive and flexible design language which makes Magic special among its peers. And that kind of magic is something rare we have to appreciate when the opportunity arises.

Tom’s fate was sealed in 7th grade when his friend lent him a pile of commons to play Magic. He quickly picked up Boros and Orzhov decks in Ravnica block and has remained a staunch white magician ever since. A fan of all Constructed formats, he enjoys studying the history of the tournament meta. He specializes in midrange decks, especially Death & Taxes and Martyr Proc. One day, he swears he will win an MCQ with Evershrike. Ask him how at @AWanderingBard, or watch him stream Magic at twitch.tv/TheWanderingBard.