Even in an epic fantasy card game like Magic: the Gathering, populated by giants, dragons, angels, titans, krakens and demons, labeling something a “god” creates an extra layer of expectation.

A god card has to feel powerful, and in a unique way that sets them apart from other high-impact creatures. Some games might elevate them above the mere mortals by making God a new card type altogether. However, Magic already has Planeswalkers occupying that design space — so how can you carve out a space for gods in the middle?

OLD TESTAMENT

For a very long time, Magic simply avoided the challenge of designing god cards altogether. The plane of Dominaria is not one where deities play a major part, and even immortal beings like Gaea and Yawgmoth were never referred to in religious terms.

Perhaps Wizards of the Coast was simply cautious about the PR ramifications of using the G-word lightly. Demons and other “unholy” imagery were also kept off of cards throughout many early sets.

With time, though, designers did begin to experiment with cards that were at least god-adjacent — even if they weren’t quite ready to put that in the type line. The Incarnation cycles that appeared in Judgment (and beyond) captured the idea of a “presence” bigger than the creature itself, each one representing a concept that would then benefit your other creatures from beyond the grave.

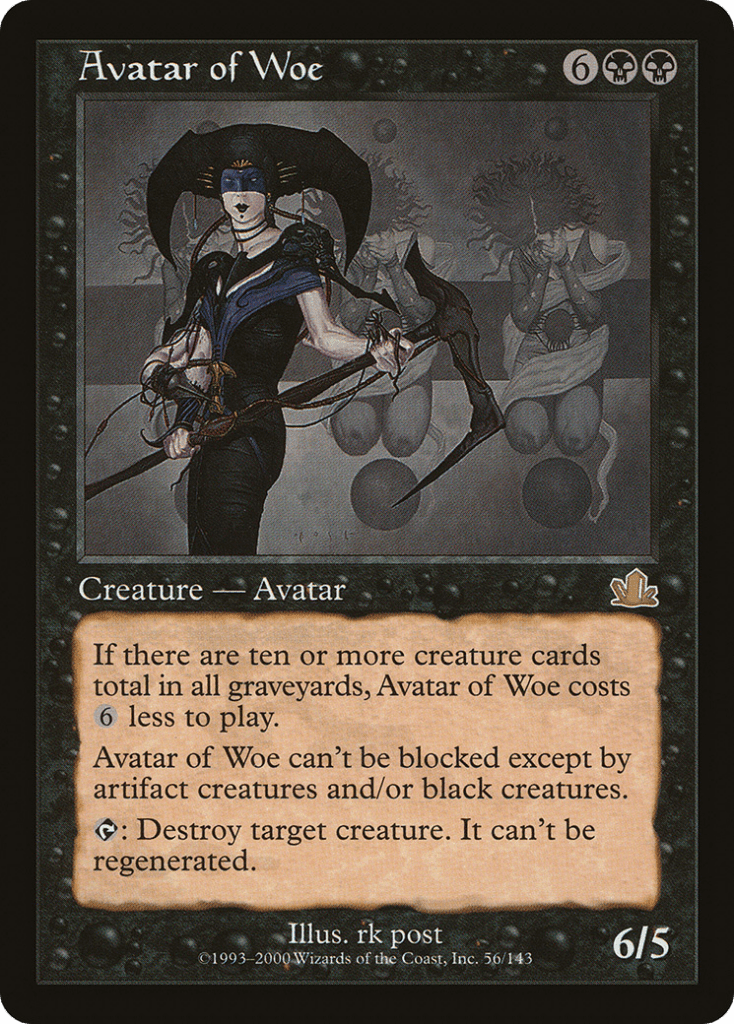

The Avatar cycle from Prophecy, meanwhile, offered players godlike stats and abilities that would only be affordable to cast when thematic in-game conditions were achieved. Champions of Kamigawa seemed to genuinely attempt a god card cycle with the Myojin, but the results can at best be described as a “rough draft.”

Nigh-impossible mana costs and “divinity counters” still didn’t feel like enough to set them apart from ordinary creatures — although conditional indestructibility turned out to be a good start. In fact, all of these experimental sort-of-god-cards have ended up contributing ideas to more recent designs, as we will soon see.

DIVINE INSPIRATION

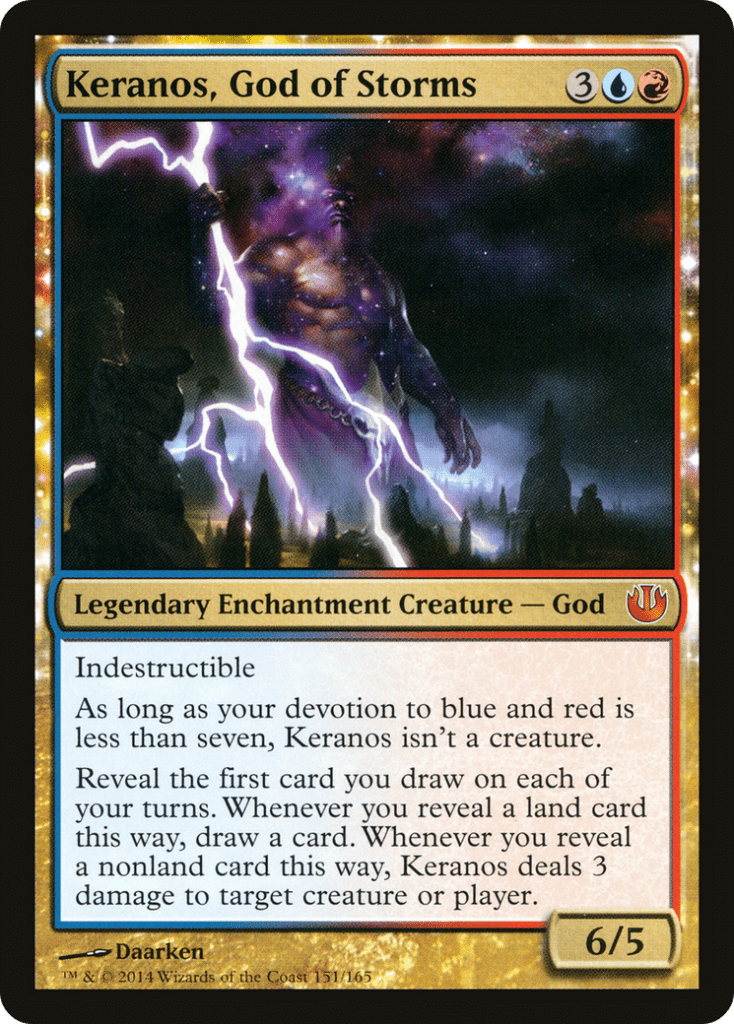

The catalyst for Magic to finally take a leap of faith and introduce actual god cards was its turn toward real-world mythology. Wizards might have avoided the divine when building Dominaria, but there was no way they could ever realize their vision for Theros without a proper pantheon.

The entire premise of the plane was centered on the relationship between gods and their worshippers, with the power of the former dependent on the belief of the latter. Huge credit to the Theros design team for this, because they were able to turn that into the solution god cards had been waiting for all along!

The 15 Theros gods combined the universal “presence” effects of the incarnations with the indestructible might of the myojin — but they couldn’t attain full power unless shown the proper devotion. That drawback meant the designers could give the gods extremely low casting costs compared to their potential, creating exciting, competitive cards that felt worthy of the creature type.

That set the formula for Amonkhet’s god cards a few years later; hard-to-remove creatures that can only affect the battlefield through abilities until their followers are assembled.

This time those abilities are activated rather than static, to reflect the more direct physical presence of the gods in Naktamun society — but there was still a clear connection that cemented the design rules for god cards in the future. Naturally, the next few cycles would immediately break them!

TWILIGHT OF THE GOD CARDS

Hour of Devastation introduced Amonkhet’s other, forgotten gods, now corrupted and eternalized by Nicol Bolas. The fact these gods had been defeated in the lore made in-game indestructibility inappropriate, so they instead gained a zombie-like knack for returning from the graveyard. They also lacked any kind of “devotion clause,” now sustained by the magic of Bolas rather than mortal worship.

This undead variant of god card continued with the zombified God-Eternals in War of the Spark, and Ilharg, the Raze-Boar (a deity unrelated to Amonkhet or Bolas) coincidentally also returned from the dead for that set.

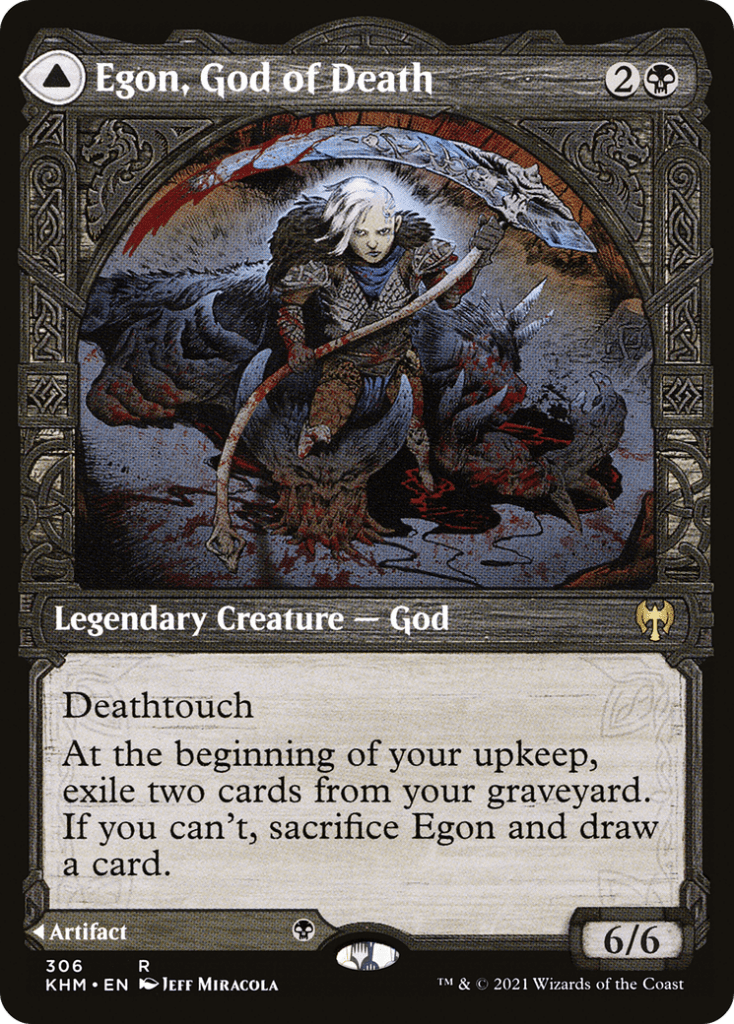

The next set to feature god cards was Theros: Beyond Death, which naturally returned to that plane’s established template of indestructible enchantment-creatures. But after that interlude, Kaldheim’s norse-inspired design gave us Magic’s most fragile gods yet.

Compared to their counterparts in the Egyptian and Greek pantheons, myths of the Norse gods show that they can die as mortals do — in fact, it is their certain destiny at Ragnarǫk. Those myths also tend to show gods interacting with peers within their own realms, rather than bringing their outsized influence to the world of men.

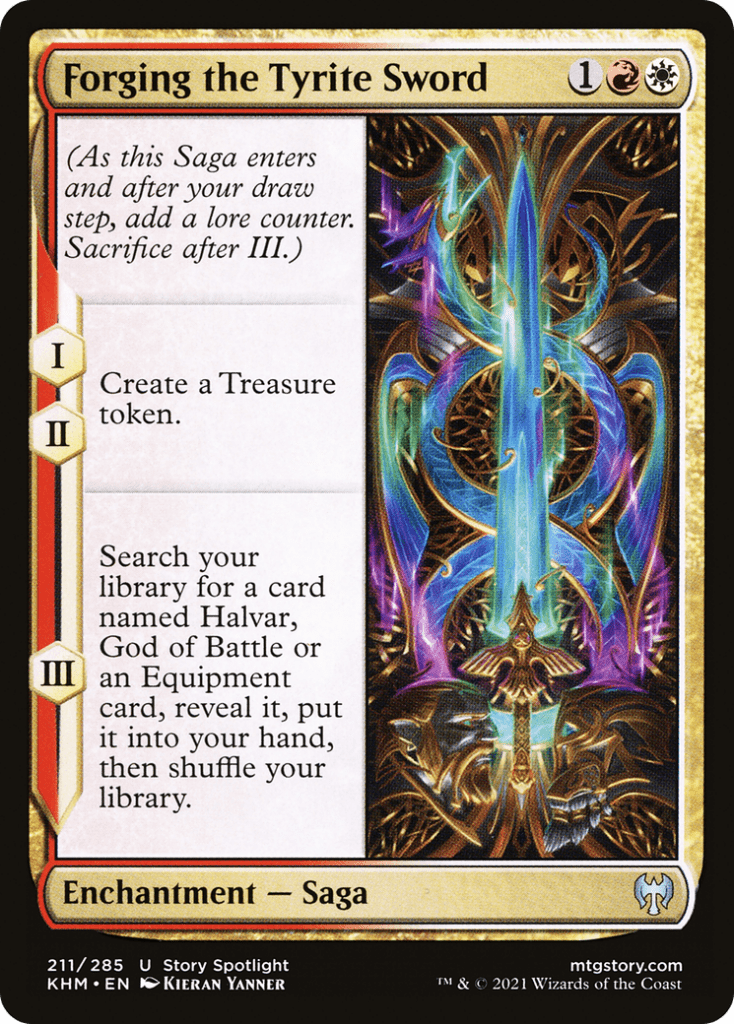

Kaldheim inherited these setting details, all of which led to a cycle of gods that completely ignored the precedent laid out by Theros and Amonkhet. But with the hard work already done to establish the design language of god cards, this decision feels more like a thoughtful subversion that sets the Kaldheim gods apart.

NEW AGE BELIEFS

Nowadays, Wizards is iterating on that design language several times a year, although more as incidental one-offs than the previous, large cycles. The exact combination of godly attributes continues to shift with the lore and setting.

Svyelun of Sea and Sky is goddess to Dominaria’s merfolk, finally acknowledging the pantheon of Magic’s original plane as equal to that of Theros.

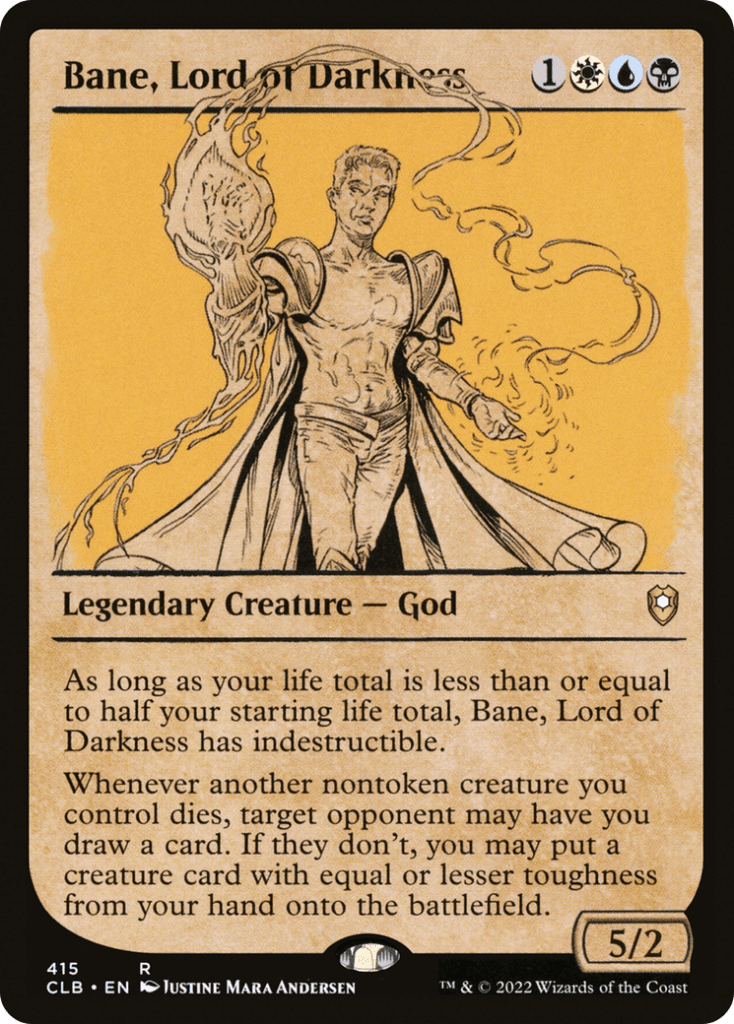

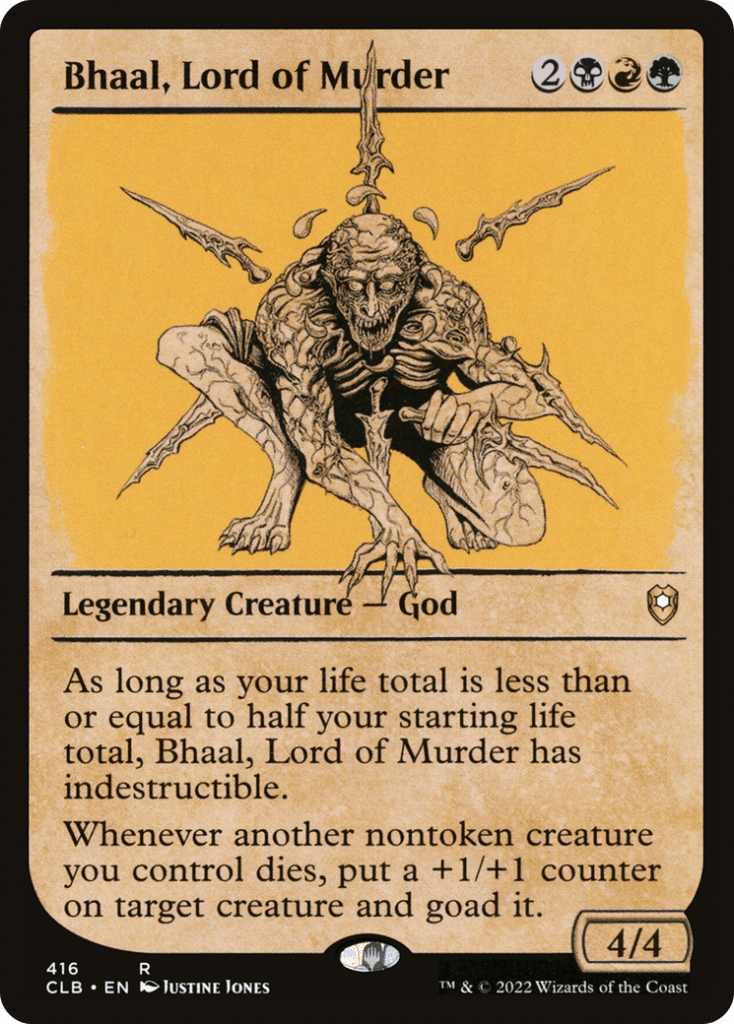

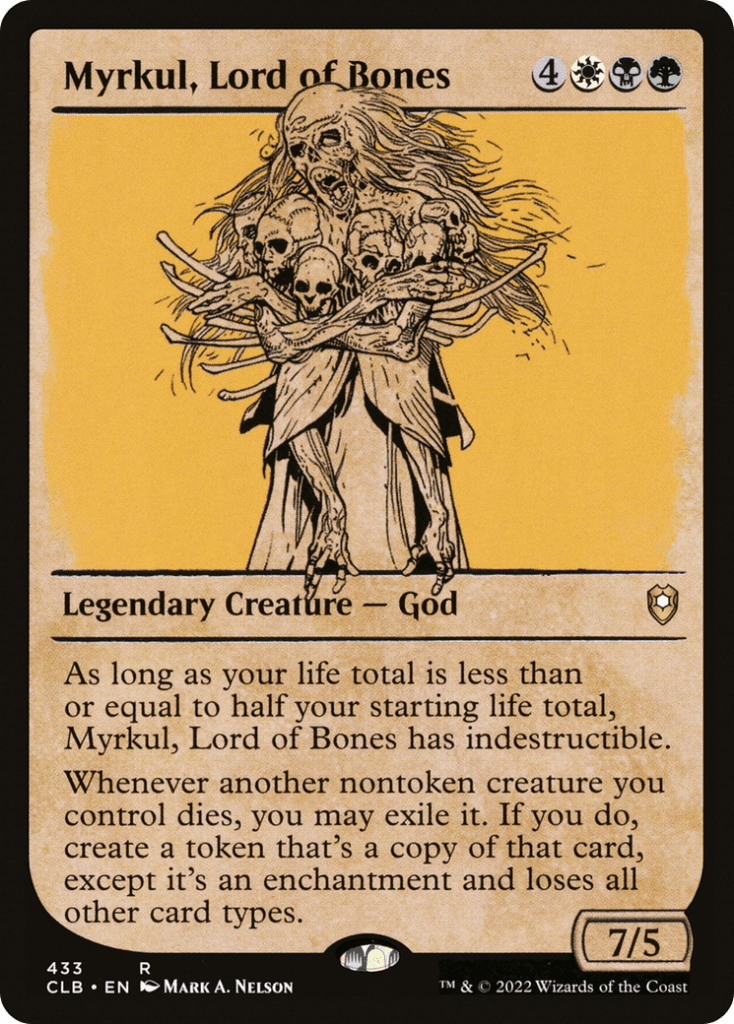

Meanwhile the infamous “dead three” of the Forgotten Realms are mortal adventurers who took advantage of a crisis to ascend as gods of death — reflected in how they gain godlike indestructibility as life totals fall.

Ephara, Ever-Sheltering draws her indestructibility from the enchanted fabric of Theros rather than mortal devotion, while the doomed Heliod, the Radiant Dawn lacks any of his previous markings of divinity.

Djeru and Hazoret and Inga and Esika clearly take after the human half of their legendary pairings, while Tiamat and Asmodeus the Archfiend are gods more in the Kaldheim mold of “powerful extraplanar beings” than deific figures of worship.

Finally, Magic’s take on Tom Bombadil astutely frames him as a godly being whose immortality depends on song and story.

DEITIES FROM THE DEEP

That brings our potted history up to the present day, where we are anticipating our first new planar pantheon in some time.

Ojer Axonil, Deepest Might appears free to attack and block as a creature without any support or devotion from other cards, just like his fellow “forgotten” deities from Amonkhet. But instead of true indestructibility or even the God-Eternals resurrection clause, his form of godly resilience is to temporarily transform into a land when slain. Performing the appropriate rituals to appease the Deepest Might at his temple will then allow him to be reincarnated, transforming to his creature side once more!

It’s a very flavorful concept that still ties back to the fundamental idea of god cards invented for Theros, and I’m excited to see how the remaining Core deities will play out in Standard and beyond.

PLAYING GOD(S)

I haven’t talked much about the gameplay of gods in this article, which is just as important to successful card design as establishing their consistent identity in Magic. As creature types go, gods are in a uniquely exciting spot right now.

Any individual god can be the centerpiece of a deck built around their strengths, but Wizards has also carefully orchestrated things so there are incentives to play an all-gods deck in non-rotating formats like Commander.

For starters, having all 15 original Theros gods in play will fulfill all their “devotion clauses” without any extra help (as well as those for the seven gods from the latter Theros block, Ephara, Ever-Sheltering, Oketra the True and Rhonas the Indomitable)! How do you get that many expensive gods into play at once? How about The World Tree’s oft-forgotten second ability?

You can easily fit all this into a commander deck under fellow deity Esika, God of the Tree, both sides of which are tailor made for a deck heavy on multi-colored legendary creatures. You can also lead with a more typical all-legends commander like Sisay, Weatherlight Captain or Jodah, the Unifier.

There’s the option to throw in some flavorful self-mill sagas like Tymaret Calls the Dead, The Binding of the Titans or Death in Heaven and then scoop your gods out with type-sensitive mass reanimation from Patriarch’s Bidding, Haunting Voyage, Replenish, Resurgent Belief or Primevals’ Glorious Rebirth. Find enough relevant sagas and you can even justify fitting Tom Bombadil in alongside his motley crew of divine kin!

An all-gods typal deck is admittedly short on synergistic effects, but that almost becomes a strength with cards this powerful. Much like the all-planeswalker “superfriends” archetype, its strength is in having a huge toolbox of independently strong effects that are all enabled in roughly the same way.

There’s also very few gods that actually fall off when surrounded by their kin. Tiamat, Bontu the Glorified, Toralf, Svyelun and perhaps Tom Bombadil make the list.

Even gods like the Dead Three (Bane, Lord of Darkness, Bhaal, Lord of Murder and Myrkul, Lord of Bones), which rely on your creatures dying, can find value thanks to the refreshingly-perishable Kaldheim gods!

Whether you do pack your deck with multiple pantheons or dedicate your worship fully to one favorite deity, the overwhelming majority of post-Theros god cards feel like they deliver on the tabletop. It may have taken a few decades of design expertise for Magic’s creators to tackle this daunting assignment, but in the end they’ve made believers out of us all.

Tom’s fate was sealed in 7th grade when his friend lent him a pile of commons to play Magic. He quickly picked up Boros and Orzhov decks in Ravnica block and has remained a staunch white magician ever since. A fan of all Constructed formats, he enjoys studying the history of the tournament meta. He specializes in midrange decks, especially Death & Taxes and Martyr Proc. One day, he swears he will win an MCQ with Evershrike. Ask him how at @AWanderingBard, or watch him stream Magic at twitch.tv/TheWanderingBard.